x

“All signs and proofs show that we have passed the historical daytime era and entered the night-time era.” This was written a hundred years ago, but could just as well be said today. In 1924, the Russian religious philosopher in exile, Nikolai Berdyaev (1874–1948), published the essay Novoe Srednevekovie (The New Middle Ages) in Berlin. In view of the Russian Revolution and the First World War, the essay signalled a dramatic break between epochs: a transition from the rationalism of the modern era “to an irrationalism, or better, to a super-rationalism, of the mediaeval type.” Resonating with the apocalyptic mood of its time, the text proved an immediate success and was soon translated into major languages, including German, French, English, and others.

While Berdyaev did not mean a literal return to the Middle Ages, he argued for a step forward into a new mediaeval age, one that would draw on the accumulated human experience of past epochs. Despite the era’s prevailing anxiety and fear of the present, he remained optimistic about what the new period might bring. “The Middle Ages was not a time of darkness, but a period of night ... Night is not less wonderful than day; it is equally the work of God. It is lit by the splendour of the stars and reveals to us things, elements, and energies that the day does not know. Night is closer than day to the mystery of all beginning.” In his essay, the philosopher anticipated a green economy — one returning to nature and an artisanal mode of production — as well as a shift from nation-based societies towards a more universal, spiritual fraternity: seemingly mediaeval concepts and practices reimagined. Yet the overtly religious framework of his essay somewhat diluted his otherwise insightful vision.

A novel wave of neo-mediaevalist sense of time resurfaced again towards the end of the twentieth century, particularly in political thought. Meanwhile, the Italian scholar Umberto Eco (1932–2016) became perhaps the most prominent observer of this revival in literature and culture — notably through his essays “Dreaming of the Middle Ages” and “Living in the New Middle Ages” (both 1986).

This research-based art periodical argues that a neo-mediaevalist trend has emerged within the domain of contemporary art. The core evidence for this speculation lies in a recent development, which some critics and curators trace back to the mid-2010s. As yet, it lacks a generally recognised international name. In the very east of Europe, it is known as aggregator art. The term derives from content aggregator websites, which gather exhibitions, artists, and works that largely represent and promote this novel aesthetic. Among the oldest and best-known online platforms are ofluxo.net (since 2010), kubaparis.com (since 2013), aqnb.com (2012–2022), tzvetnik.online (2016–2023), saliva.live (since 2017), Tired Mass (since circa 2019), and others.

At first glance, aggregator art appears to be a material, object-based, figurative (but not realist) visual practice with an evocative sense of mediaeval sensibility — kustar-like, handicraft, and artisanal in its aesthetic — despite its frequent use of contemporary materials and technologies such as 3D printing. Its subject matter is often hermetic, esoteric, alien, gothic, dark, or pop-folkloric, and frequently echoes the logic and aesthetics of video games — arguably a form of folklore in the digital age. This trend is often linked with contemporary philosophical theories such as Speculative Realism and its subset, Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO), Cyberfeminism, or discussed in the frameworks of the Post-Anthropocene and Post-Apocalypse. Some commentators view it as revolutionary; others dismiss it as reactionary, citing a perceived formalism and a lack of overt critical or political engagement.

This art periodical will explore this trend and its discursive dimensions — including protagonists, exhibitions, settings, habitat, texts, sources, events, manifestations, vocabulary, and so on. It will also test whether the most original and “neo-mediaeval” quality of aggregator art lies in its morphology. One might argue that its mature examples represent an amalgamation (the alchemical connotation is deliberate!) of “applied” and “fine” art properties within a single work or installation — to such an extent that neither category fully exhausts nor defines the perception of the work as a whole. (One of the most common mediaeval examples of such an amalgamation is, perhaps, the icon painting.) In his provocative book The Invention of Art (2001), American cultural historian Larry Shiner demonstrates that the accepted conceptual and institutional divide — or, in his terms, the Great Division — between decorative and fine arts was a radical invention of the modern era. The establishment of academies, exhibitions, museums, and the emergence of art theory (aesthetics) gradually cemented this distinction by the end of the eighteenth century. Aggregator art, then, seems to echo a time when no conceptual division existed between applied and fine arts, nor was such a division practical or meaningful for the production and perception of art.

Of equal interest to us is the broader field of collateral contemporary art practices that resonate with aggregator art, expand its immediate context, and bear a neo-mediaeval resemblance: an interest in magic and occultism, noise music, folklore, the cult of death, cloth-making, lacework, tattooing, among others.

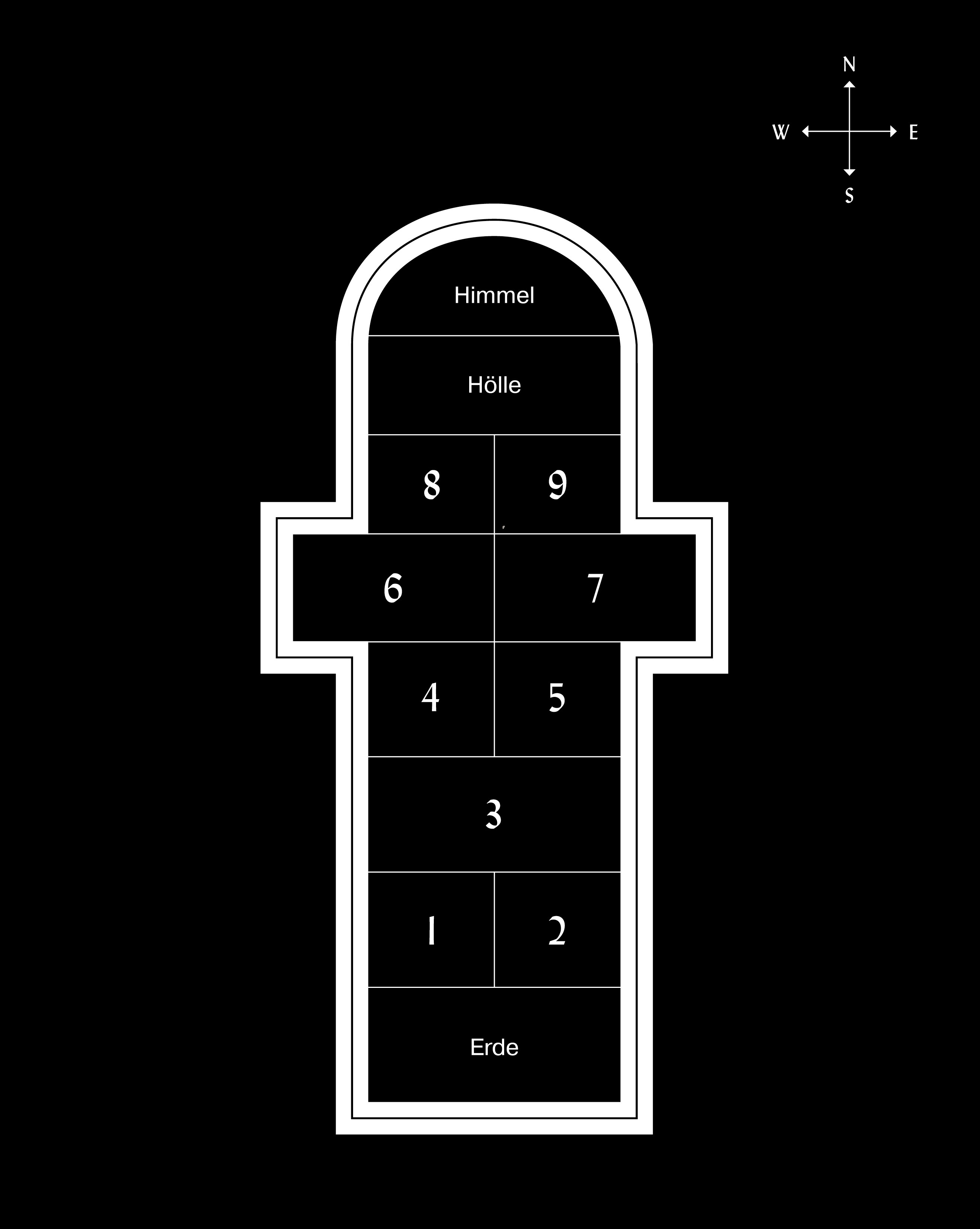

Unsurprisingly, this new art trend is often at odds with the modernist white cube, let alone with museums. It favours instead pop-up shows in unconventional settings: shop windows, clubs, shelters, catacombs, garages, abandoned sites, forests, and, of course, churches — the principal public art space of the mediaeval era.

Lastly, this novel trend in art appears to align with broader technological and socio-political developments of our time — developments that, in many ways, echo our imaginary Middle Ages: green energy, neo-feudal corporate structures, mass migration, epidemics, and wars.

Hence, methodologically, this research-based art periodical will operate at the intersection of contemporary art, art history, literature, history, game studies, philosophy of art, social, political, and migration studies, the natural sciences, the green economy, and related fields. By following the young protagonists of these new developments in art, the periodical aims to situate their practices and narratives within a broader and timely social, technological, and aesthetic context — at the dawn of the Night era.